Why do so many writers lump “systemic thinking” in with Design Thinking? And why are words like “holistic thinking”, or “wholism” so often invoked around Design Thinkers.

Looking at the two archetypes reveals the driver for this phenomenon. It shows why systemic thinking is more apt to be invoked in Design Thinking contexts than in Scientific Thinking contexts. Let’s be under no illusion, however. Those who DO science have a need of systemic thinking (and are unconscious practitioners of it to more or less able extents) on a regular basis.

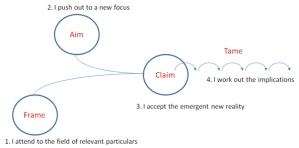

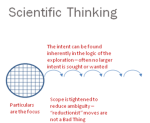

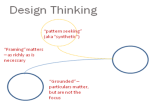

Again, back to our heuristic:

The one: and the other

Which feature of these epistemic acts, if most regularly excercised, is most likely to nurture or call upon suystemic thinking?

It is the task of Framing:

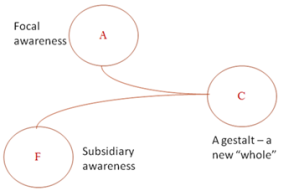

More technically, “Systems Thinking” is the capacity to conceptualise large spaces – literally, to turn large amounts of related information into concepts. Here we come to another critical term in our epistemology – the “concept”.

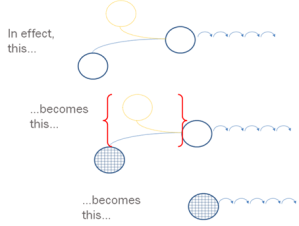

George Miller popularised the research showing that the mind had a finite capacity to hold and manipulate concepts – that finite capacity being “The magical Number Seven, plus or minus a few”. And while memory champions use tricks to regurgitate staggeringly long arrays of information, and a few savants (such as the original “Rain Man” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kim_Peek ) display sticky memories that put the Wikipedia back into human perspective, the truth is that most of us, no matter how sharp, are bound by that 5 – 12 item reality. But here’s the trick. These 5 – 12 items are not things, or brute factoids. Not like the party trick (eg http://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/chmemory.html) with the mixture of kitchen items – unitised physical objects such as a peeler, a cork, a whisk. No. The memory functions with the “names” of things – with the concepts that “label” bunches of allied information. So if we can make the bunches we hold under these conceptual labels bigger, then we can hold and manipulate more “stuff”. So how do people handle higher and higher complexity as they grow more experienced in a subject matter (eg scientists), or as they tackle big new fields of information (eg designers)? They do it by changing what they can fit inside a single concept.

Scientists do this bunching by their highly honed lexical stock. They use shorthand all the time – which is why technical texts are often incomprehensible to lay people no matter how “plain Englished” they are. Manipulating the “voice” the text is written in, or using plainer verbs doesn’t change the way the concepts are constructed. It’s also why techos prefer their own company – they can stride across large technical landscapes using their shorthand. Their fluency crashes to the floor when confronted by the need to slow their airspeed while they unpack each of their technical terms for a lay listener.

And so to the relevance of systems thinking to Design Thinking. A system is a way of conceptualising a large bunch of stuff – of treating it as a whole because we understand it as a whole through its connections and interdependencies, not as a zillion disparate independent particles.

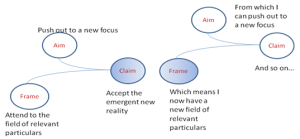

And what Design Thinking has to be able to do is hold the Frame as a whole (or close to a whole) in order to move out from that ground to a new focus.

So Systems thinking is the ability to take large pieces of reality, see the theme and name it, and thus reduce the pieces to manipulable dimensions

Not only is the need for systemic thinking – for using the tools of systems thinking – more apparent and inescapable in Design Thinking, it has to be accepted that it is less likely to happen in a world where the dominant thinking styles are Scientific Thinking. Look at that model again:

The movements of mind toward analytical decomposition and inferential extension don’t foster holism. In fact Ian Mitrof wrote: “The extent of fragmentation in the minds of trained scientists is such as to require therapeutic invention”. (Mitroff http://mitroff.net/about/ was the President of the International Society for the Systems Sciences – this quote reconstructed from 1992 memories – another one of those seeringly memorable quotes from the days when everything didn’t end up in on-line searchable repositories).

it has tried to understand its identity and characterise its offer in terms of Scientific Thinking

it has tried to understand its identity and characterise its offer in terms of Scientific Thinking